Antimicrobial agents are key weapons in our arsenal against diseases in humans, animals, plants, and crops. As resistance to these agents increases, we are facing a serious challenge to the healthcare advances we have made over the last century. Routine infections are becoming more difficult to treat and critical medical procedures and surgeries are growing increasingly risky. (UN IACG, 2019).

The antibiotic market distortion

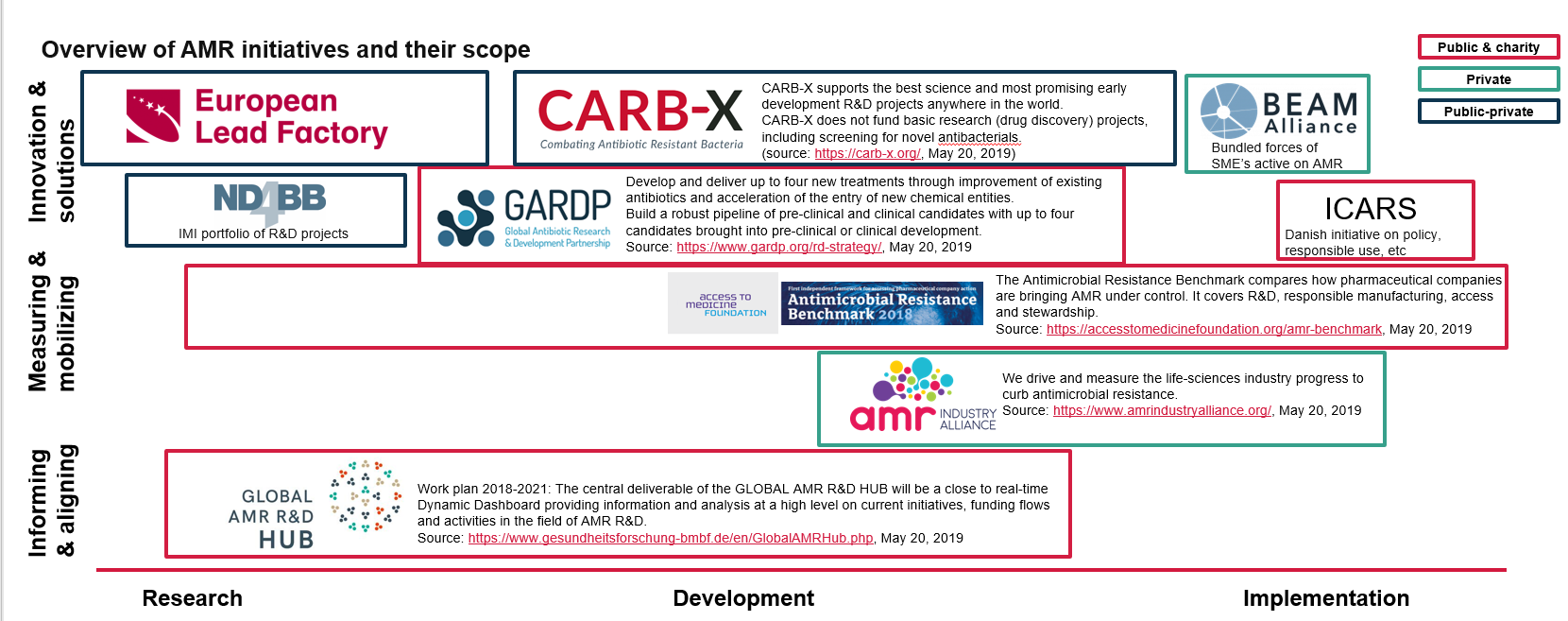

Antibiotic development is a time consuming endeavour that has no guarantee of results. Because of these risk factors, new drug development requires significant incentives. Developing a new antibiotic can take over a decade and cost more than €850 million (Drive-AB, 2018). It can generally be divided into two main phases: initial R&D development, which is mostly done by SMEs and public institutions including research institutes and universities, followed by drug development and testing, which is done by larger pharmaceutical companies. The AMR Industry Alliance reports investment of around 2 billion USD into AMR research across 22 companies in 2018 (AMR Industry Alliance, 2018). While a number of companies are producing antibiotics (IFPMA, 2015) (Access to Medicine Foundation, 2018), many of them are variations on existing antibiotics. These ventures are a safer bet for companies to invest in because less research is needed and approvals are faster due to similarities to existing approved drugs. However, these slightly modified antibiotics only overcome resistance for a short period of time. Research into novel antibiotic classes is very low.

As our last-resort antibiotics, such as colistin and carbapenem, lose their efficacy (CIDRAP, 2017) (Meletis, 2016), it is imperative that antibiotic R&D is prioritised so that we may have new and effective antimicrobials in time. However, these new ‘last-resort’ antibiotics would be just that: ‘last resort’. We cannot take the risk of seeing bacteria evolve resistance to them or we will be back in the current situation. They should be made for emergency use only and not to be used at a large-scale. Because of these limitations, investment in new antibiotics is very unattractive for most of the pharmaceutical companies.

In recent years the focus, both from society and the political sphere, has been on so-called ‘stewardship’ measures. These are policies and actions designed to reduce the overall use of antibiotics and they are tailormade for each sector. This is obviously an important part of the solution to the AMR problem. However, they intrinsically lead to a lesser volume of antibiotics used and therefore a shrinking market, leading to a further decrease in interest in antibiotic development for the industry due to decreasing profits. This is effectively a market failure and it is created, for the most part, through legislative instruments. This can only be repaired through the development of new legislative instruments.

This market failure has contributed to the lack of scientific innovation that has resulted in far too few new antimicrobials, vaccines, diagnostic tools, and other alternatives in the research and development pipeline for humans, animals, and plants. Countries of all income levels are reporting concerning antimicrobial resistance rates – not only “hotspot” countries where we expect to see the highest levels. In some Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries reports indicate that roughly 35% of common human infections are resistant to available treatments. In several low- and middle-income countries resistance rates are already has high as 80 and 90% for some antibiotic-bacterium combinations (UN IACG, 2019; OECD, 2018).

Environmental pollution – a problem within the supply chain

The UN Environment report Frontiers 2017: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern attributes the spread of AMR, in part, to the discharge of drugs and specific chemicals into the environment (UN Environment, 2017). Pharmaceutical residues present in the environment not only promote the spread of resistant pathogens, but also can turn typically harmless environmental bacteria into resistance carriers. Because of this, experts consider antibiotic resistance bacteria to be “the greatest human health concern” (Ågerstrand et al., 2015; HCWH Europe, 2018).

Uncontrolled manufacturing discharges leave long lasting, devastating effects on water systems and the people and animals that come into contact with them. Studies and documentaries on the topic have shown that resistant bacteria plague waterways in countries where this problem is at its peak, such as India and China where most APIs and manufactured. (Changing Markets, 2016; Larsson et al., 2007; Lübbert et al., 2017; Al Jazeera, 2016; Larsson, 2014).

Other studies out of Hyderabad, India have found disturbingly high concentrations of pharmaceuticals in waterways that far exceed safe exposure levels and regulatory maximums (Larsson, 2014). Point-source pollution occurs in specific areas where the production of APIs and finished dose antibiotics take place which causes excessively high concentrations in these locations that encourages the development of drug resistance. For vulnerable populations living near manufacturing facilities and wastewater treatment plants this practice can have serious health ramifications.

In Hyderabad specifically, a recent study indicates pregnant women from low-income backgrounds exposed to these polluted areas are at a significantly higher risk for community acquired-antimicrobial resistance (Aslan et al., 2018). India is critically affected by the contamination of water sources with antimicrobial drugs as well as widespread misuse of antibiotics and poor sanitation; an estimated 58,000 newborns die each year from multi-drug resistant infections there (Laxminarayan et al., 2013; HCWH Europe, 2018).

What is the role of economic investment in Research & Development in AMR?

What is the role of economic investment in Research & Development in AMR?

Report

Report